In ‘The Idiot’, Dostoyevsky describes the main protagonist, prince Myshkin:

his eyes were large and blue, and had an intent look about them, yet that heavy expression which some people affirm to be a peculiarity. as well as evidence, of an epileptic subject.

However, this does not square with modern medicine, which rejects the notion that epilepsy can be traced in a person’s looks, so I wonder if Dostoyevsky had something entirely different in mind?

I (think I) know that Epilepsy was considered a ‘sacred disease’ in antiquity and this seem to agree with the rest of Dostoyevsky’s portrayal of Myshkin (especially given Myshkin’s life-saving seizure when he is put under great stress by being threatened), but I doubt that medical science in Imperial Russia hadn’t already given up any such notions of the disease?

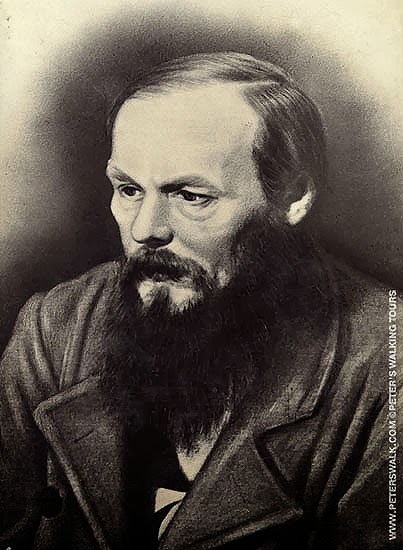

The most relevant data point here is that *Dostoevsky* had epilepsy. He first started having seizures–generalized tonic-clonic (grand mal) ones–in prison in the 1850s. (Some people have speculated he presented with other types of seizures earlier; there’s a whole debate about what specific seizure disorder he had, because of course there is). So we’re working with a pretty specific data set given the immediacy of the issue: other people’s descriptions of his own seizures to him, of which plenty survive.

In “The Insulted and the Injured,” Dostoevsky writes in a character with epilepsy, Nelly, who (like his son) developed seizures early in life. He describes a tonic-clonic seizure…but then goes even more extensively into the aftermath. Often, tonic-clonic seizures and complex partial seizures are followed by a period of confusion and grogginess known as the “post-ictal” state; I generally describe it as swimming back up to full consciousness and passing out as soon as you get there. Dostoevsky, however, has a far more poetic way to describe it from the outside:

> She looked

at me for a long time without any motion, but with

high tension, just as she tried to understand something.

But it was obvious that it was troublesome for

her. Finally, something like a thought enlightened

her face. After an attack, she usually could not think

clearly and only mumbled inapprehensible words.

That seems to track with the “heavy expression” of Myshkin–post-ictal grunkiness rather than a connection with mental illness (epilepsy is often comorbid with a whole range of neurological and psychiatric conditions) or the ictal (active) state of a complex partial seizure.

Just for kicks, I did a quick scan of Google Books from 1800-1850, and it looks like English-language literature uses “epileptic expression” to describe the post-ictal period as well.

~~

Addendum: Good heavens, there is a larger body of academic scholarship on Dostoevsky and epilepsy than there is on several of the authors I study in my dissertation. What a world.

Whaddaya Say?